By Courtney Warren

Recently, I had the opportunity to travel to Florida and represent my school at the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts. With two of my colleagues, Dr. Danielle Bray and Prof. Sarah Gibbons, we talked about the need and want for students to have access to books that feed the imagination.

In her timeline of the Newbery Medal, Kathleen T. Horning cites as one factor leading to the award’s foundation the suggestion by the then-head librarian of the Boy Scouts of America that the American Booksellers’ Association host an annual Good Book Week for children to counteract what he considered “the poor quality of boys’ reading” (12).

Over a century later, his concerns persist. A search for “reluctant readers” and a secondary term such as “quality” or “literary” yields articles from scholarly journals, trade publications, and even local newspapers in which authors bemoan the difficulty of convincing students to read texts of purported literary quality or of enticing “reluctant readers” to pick up a book at all.

Adult stakeholders and even students themselves often argue about what actually “counts” as reading, marginalizing noncanonical texts in favor of literary-voiced realism and so-called “classics” (Good D8; Gutchewsky 79-80; Hawk D5; Joseph O18). In such arguments, there is dissonance between the desire to empower student choice and the fear that their choices will not be “good.”

Frequently, teachers advocating student choice use a pre-set list to ensure that what students are choosing is “good enough” (McGrath), “not junk” (Finn L1), or otherwise sufficiently literary (Gutchewsky 79-80; Joseph O18).

Among those writers who celebrate children reading at all, the marginalization persists, with one journalist conceding that what reluctant readers self-select is “not Dostoevsky” (Hawk D5), and another suggesting child-selected books be offered as a reward for reading a canonical text (Hardin 6). Some even make claims that positive books are a no-go. One source warns that reluctant readers “are not interested in warm and fuzzy books” (Hardin 6), and an educator colleague reports concerns from their school administration that reading positive stories lowers students’ ACT scores.

In spite of gatekeepers’ fretting about literary quality, studies support the idea that true student choice is key in fostering a reading habit (Doiron 44; Gutchewsky 80-82).

Paul Register, founder of the UK’s Excelsior Award for outstanding graphic novels, has a student panel vote on the award and warns against pushing students toward titles that are acclaimed by critics and other adults but unpopular with children themselves (8-9). Researchers also agree that exposure to diverse genres is a key element of literacy instruction (Deitcher et al. 294), and that a “whole literature” pedagogy encourages students to read everything they encounter, from both efferent and aesthetic stances (Doiron 39-41).

For all of these reasons, and because studies show that reluctant readers are drawn to fantasy (Goldman 38, Hardin 6), we argue in favor of offering genre fiction to student readers. Such fiction presents challenging vocabulary and difficult concepts in a medium that is attractive to most students (Register 8), and, according to our conversations, student readers simply find fantasy stories fulfilling.

Based on a myth-critical approach grounded in the works of Joseph Campbell and Gail Carriger, supplemented with student interviews, we analyzed the particular benefits, both curricular and social-emotional, of using fantasy literature in the English-Language Arts classroom.

My favorite part was sharing the thoughts of my students on the importance of having exciting classes and great books to read.

One student said, “When students are solely assigned literary fiction and classics, it’s easy for them to lose focus and interest, because they’re often uninteresting and repetitive. But fantasy books give a wider scope for the imagination, and they engage readers, while also subtly teaching lessons about morals and ethics. Fantasy books also have more potential of appealing to a larger audience, due to the fact that they are not confined to realism and set facts.”

This student is in the seventh grade! How impressive is that?

Another said, “We already have enough stress with real world problems, and reading fantasy is good, because we get to be distracted from the real world.”

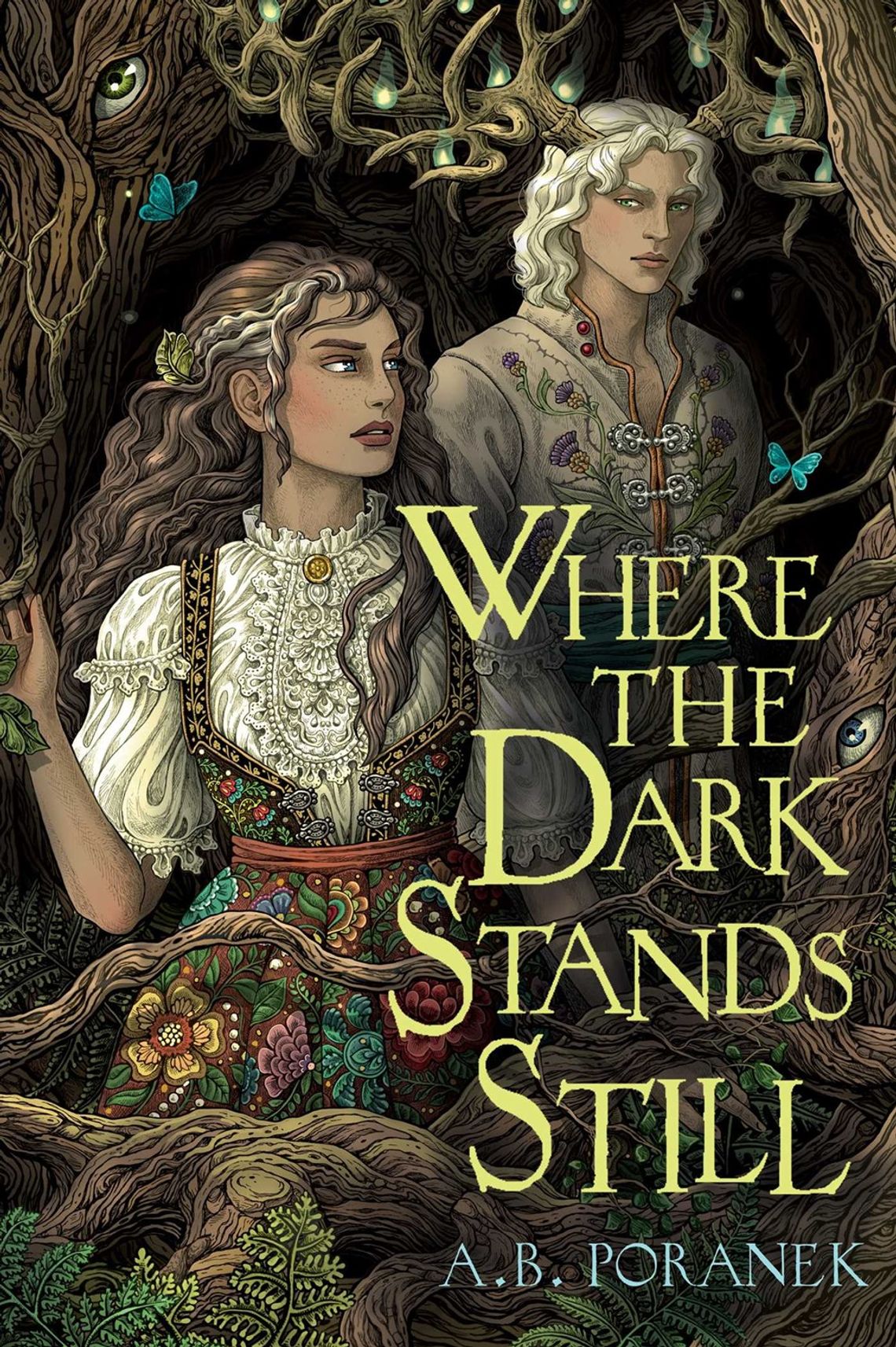

So, with that in mind, this month’s on the shelf recommendation is Where the Dark Stands Still, by AB Poranek. It’s a gorgeous Polish retelling of Beauty and the Beast.

According to the publisher, raised in a small village near the spirit-wood, Liska Radost knows that Magic is monstrous, and its practitioners, monsters. After Liska unleashes her own powers with devastating consequences, she is caught by the demon warden of the wood – the Leszy – who offers her a bargain: one year of servitude in exchange for a wish.

Whisked away to his crumbling manor, Liska soon discovers the sinister roots of their bargain. And if she wants to survive the year and return home, she must unravel her host’s spool of secrets and face the ghosts of his past.

Those who enter the wood do not always return…

.png)

Comment

Comments